This article shows how different aspects of shape and space are fundamental to children’s lives. From the earliest years, as children navigate around their environment, they must learn about near and far, up and down, round and straight, and much more. Adults can help to extend and make explicit their children's ideas about spatial relations, which is a more complex and challenging topic than usually assumed. Educators can use many different activities and approaches, including intentional teaching, to foster learning of spatial relations.

Monique, like many young toddlers, loved emptying and filling everything. She filled pots and pans with wooden blocks, took the lid off her shape sorter bucket and filled it with rubber balls, and she delighted in emptying her small basket of toys. At the same time, through interactions with caregivers she was learning positional words and phrases such as in, on top of, and under. Shortly after her second birthday, while playing with her wooden block set, she noticed a sphere lying next to the base of a cone, and announced “i-skeem!” excitedly. Her mother, looking over, took a minute to realize that Monique saw what looked like an ice cream cone in the arrangement of blocks. At school several months later, Monique was burying toys in the sandbox. Teacher Jorge watched as she hid two small toys. After talking with her about “seeds” (they had read The Tiny Seed by Eric Carle earlier that morning), he watched as she accurately retrieved both toys from where she had buried them.

What is this all about? What do positional words, three-dimensional shapes, and buried toys have to do with each other? Our visual and tactile world consists of objects situated in space. Gaining an understanding of the attributes of those objects and where they are (and especially how we can get to them!) are some of the most important aspects of development in a young child’s life. Knowledge of object categories and attributes allows children to mentally and physically organize things in their world; spatial awareness and spatial relations allow children to locate objects and navigate successfully in their environments; and using spatial language enables children to express their needs and concerns (“Oh no, Mama! Teddy under bed!”) and describe and discuss the world around them (“If you put the triangles together, they make a square!”).

We are born spatially aware. At birth, we can discern and track our parents’ movements. Minutes after birth, infants are more likely to track a human-like face than a blank head outline, and prefer face-like patterns to patterns in which facial features are scrambled, suggesting that they can discriminate between the two. Even at this young age, humans pay attention to features of objects. Before young children have the words to describe on top of or under, they have the ability to distinguish the difference between a picture where dots are above a line and one where dots are below a line. Learning one’s left and right hands is a notoriously difficult task for many young children. However, by age four-months, infants notice the difference between a picture where dots are to the left and one where dots are to the right of a line. And just a few months later, they differentiate not only left and right, but between as well.

Let’s dissect some of these skills and abilities and examine what they mean in the growth of a young child’s mathematical development. We’ll begin with children’s increasingly sophisticated perceptions of objects/shapes and their attributes, then explore physical and mental manipulation of those objects/shapes (orientation and mental transformation) and navigation through space, and we will finish up with spatial language.

By about 18 months of age, children’s acquisition of vocabulary increases greatly. (This period is sometimes called the vocabulary explosion.) This acquisition includes a rapid expansion in the ability to verbally name and categorize objects, although the meaning of words often changes during this period. For instance, the meaning of dog may change from denoting only the family pet to all animals that are furry, have four legs, and a long nose. Children’s developing cognitive skills also allow them to see only part of an object, for instance Rio’s nose peeking out from under the bed, and ascertain that even though only a nose is visible, it is attached to a dog. Even infants can hold in memory a representation of Rio, and know that when Rio is observed in a variety of representations (sitting down, jumping up, trying to catch his tail) and partial views (wet nose only) he is still Rio. Children become capable of recognizing objects in different orientations, illustrating their developing spatial knowledge.

When children have opportunities to explore two- and three-dimensional objects, they develop an ability to coordinate movement and alignment of these objects. This can clearly be seen when they align a triangular prism in order to push it through the triangular-shaped hole in the shape sorting bucket. When children have ample opportunities to explore their environments, resulting in the gain of greater and greater fine and gross motor control, they learn to both manipulate objects and navigate more skillfully. You might notice young children insisting that toys be placed in a certain location or orientation (think of a favorite stuffed animal’s regular placement at the top corner of a blanket, or a child’s demand that all the toy cars be lined up), or stipulating that they have to walk on the lines in the sidewalk. While sometimes challenging, these are all budding instances of children’s developing spatial manipulation and awareness skills. As illustrated, these skills are important and useful in children’s everyday lives, but they are also, fortuitously, early skills that are related to later mathematics performance.

When children have opportunities to explore two- and three-dimensional objects, they develop an ability to coordinate movement and alignment of these objects. This can clearly be seen when they align a triangular prism in order to push it through the triangular-shaped hole in the shape sorting bucket. When children have ample opportunities to explore their environments, resulting in the gain of greater and greater fine and gross motor control, they learn to both manipulate objects and navigate more skillfully. You might notice young children insisting that toys be placed in a certain location or orientation (think of a favorite stuffed animal’s regular placement at the top corner of a blanket, or a child’s demand that all the toy cars be lined up), or stipulating that they have to walk on the lines in the sidewalk. While sometimes challenging, these are all budding instances of children’s developing spatial manipulation and awareness skills. As illustrated, these skills are important and useful in children’s everyday lives, but they are also, fortuitously, early skills that are related to later mathematics performance.

Spatial language provides children with essential tools to describe their environments and negotiate their wants and needs (“No, I don’t want that one, I want the one under it!"). And, it turns out, adults' and young children’s use of spatial language predicts children’s skills at spatial problem solving later on. Spatial language includes words describing location/position (under, in front of), attributes (long, high, side, angle, same, symmetrical), orientation and mental transformation (left, turn, match), and geometric shape names (rectangular prism, triangle, sphere).

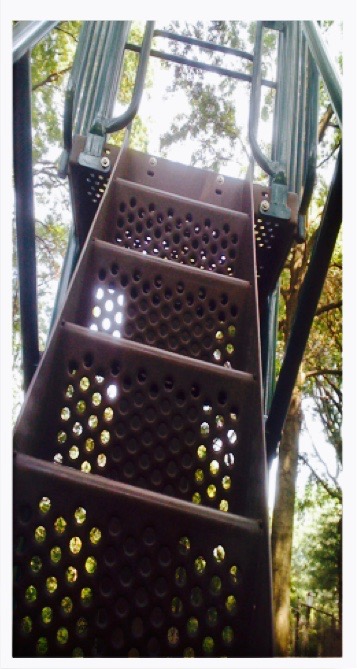

Caregivers and teachers play an important role in supporting development in geometry and spatial relations. As children spend more and more time in preschool settings, teachers need to be able to offer ample opportunities in both structured and non-structured activities that support spatial thinking and the development of geometric concepts. Fortunately, these activities can be among children’s favorites in the classroom. Non-structured activities include puzzles (orientation and mental transformation), block play (orientation, mental transformation, spatial awareness and relations), tangrams (orientation and mental transformation), and drawing and sandbox play (all of the above). More structured or teacher-guided activities include guessing the name of a hidden shape when attributes are provided (“I have a shape that has four sides of the same length and four right angles. Who can guess my shape?”), and supporting gross motor, spatial awareness and geometry development by playing Musical Shapes (a game similar to musical chairs, but with large shapes drawn on the playground that hold the same number of children as there are sides).

Although some teachers can be unnerved by their own past experiences in high school geometry, it is important to remember that young children do not bring negative experiences related to spatial reasoning to the classroom. Teachers can support children’s spatial vocabulary development through games like I Spy, asking questions like, “I spy something above the chalkboard and below the ceiling.” More advanced activities are possible too, and can support both teacher and student learning. For, just as they are fascinated by diplodocuses, tyrannosauruses and triceratops, children are also fascinated by the logic in “fancy” three-dimensional shape names. Pyramids are always named after their base, so if we have a pyramid with a square base, it is a square pyramid. Pyramids with pentagons or hexagons as bases are called (respectively) pentagonal and hexagonal pyramids. Like pyramids, prisms are named after their bases… and their tops! Prisms have the same shape at both ends, and are named after those shapes. So, a prism with pentagonal ends is called a pentagonal prism. Children pick up on these logically named three-dimensional objects and revel in their new understanding.

Although some teachers can be unnerved by their own past experiences in high school geometry, it is important to remember that young children do not bring negative experiences related to spatial reasoning to the classroom. Teachers can support children’s spatial vocabulary development through games like I Spy, asking questions like, “I spy something above the chalkboard and below the ceiling.” More advanced activities are possible too, and can support both teacher and student learning. For, just as they are fascinated by diplodocuses, tyrannosauruses and triceratops, children are also fascinated by the logic in “fancy” three-dimensional shape names. Pyramids are always named after their base, so if we have a pyramid with a square base, it is a square pyramid. Pyramids with pentagons or hexagons as bases are called (respectively) pentagonal and hexagonal pyramids. Like pyramids, prisms are named after their bases… and their tops! Prisms have the same shape at both ends, and are named after those shapes. So, a prism with pentagonal ends is called a pentagonal prism. Children pick up on these logically named three-dimensional objects and revel in their new understanding.

Like other areas in mathematics, geometry and spatial development require attention to pedagogy and content in the preschool classroom. Understanding how we can support development through the environment, materials, activities, and interactions is important. Children are excited about learning new words and ways of interacting. We should be too!