In this activity prospective or practicing teachers attempt to learn to count in a foreign language (Farsi). The experience is designed to help them understand how children feel when they learn to count, and what kind of learning is involved in mastering the counting words.

Activity for Teacher Educators

Adults may not remember how hard it was to learn the sequence of counting words, which from the child’s point of view are at first an aural blur. This activity is designed to help your preservice and inservice teacher participants gain insight into how a child struggles to learn the counting words. The task requires participants to learn to count in Farsi, a language that they are unlikely to know. Here are some instructions that you may wish to use.

Watch and listen carefully to the videos and then try to repeat the counting numbers just as the adult, a native Farsi speaker, says them.

So that was counting from one to 40 in Farsi, spoken at a relatively fast pace. Were you able to make out the individual words? Did you notice anything else?

Some of your participants may be able to discriminate some of the individual number words, particularly some of the first 10, but most will not. And even if they hear individual words, your participants will not be able to repeat them in the correct order, certainly not up through forty. Indeed, they probably won’t be able to count in Farsi from one to five. They most likely experience the words as a blur, just strange sounds that may run into each other. Ask participants to describe their experiences. Some of them may notice a pattern in the sounds, but they probably will not be able to describe it with any precision when you ask them to do so.

That was hard. But now here is a slower version counting up to 20 which no doubt you will have no trouble replicating.

Now participants will be able to hear the individual words up through ten. They will not be able to memorize them on one viewing, but just need practice. Ask participants to discuss how the Farsi words through ten are related to words in other languages. If you have a diverse class with speakers of different languages, the discussion may be very rich. For example, the word for two is something like do, which in turn is similar to the Spanish dos. The word for six is shesh, which is similar to the word for six in Hebrew.

Now that you did so well on that, here is from one to 40 spoken slowly.

What did you notice?

Now participants should be able to perceive the individual number words very well, although they need more practice to commit them to memory. But the counting gets even more interesting after dah, which is the word for ten. Participants should immediately recognize a pattern in which dah appears many times, with another word preceding it. They may see that the preceding words are similar or identical to the Farsi words for one through nine. Participants may also recognize that the Farsi words have the equivalent of this structure: ten, "one‐ten, two‐ten, three-ten, … nine-ten." The Farsi structure is like the English, although more regular. For example, the Farsi word for eleven is essentially “one‐ten,” which is more mathematically meaningful than eleven. If you have a Chinese speaker in class, participants will learn that Mandarin uses the equivalent of the words “ten, ten-one, ten‐two, ten‐three… ten-nine.” You can discuss with participants whether any of the languages are easier to learn than the others, or are better designed, from a mathematical point of view, than the others. It is likely that all languages present the same difficulty in memorizing the words from one to ten; after all, they are essentially nonsense syllables. But it is likely that Farsi and Chinese number words from eleven to nineteen are easier to learn than the English equivalents, which include the very strange eleven and twelve.

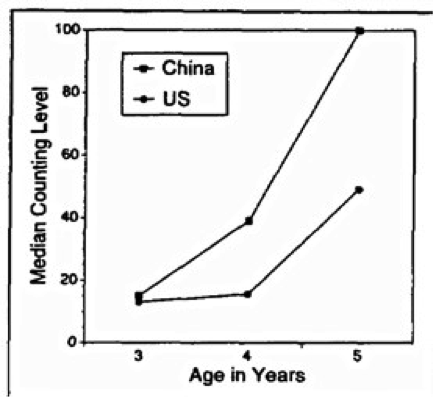

But after 19, Chinese is the most elegantly designed language of the three because it maintains a totally consistent mathematical structure: "ten, ten-one, ten-two…ten‐nine, two‐ten‐one, two‐ten‐two, two-ten‐three… nine-ten‐nine" (Miller & Parades, 1996). This figure shows how Chinese children, beginning at age four, count more accurately than American children. Why? Because the Chinese children can use the well-structured Mandarin system for numbers beginning with ten, while American children at this age have to struggle with the inefficient English language system of counting from 10 to 19.

By contrast, both English and Farsi switch the position of the ones and tens after nineteen (which is essentially “nine-ten”). Also Farsi and English have some irregular words for the tens. For example, the English twenty should be “two-ten” or maybe “two-ty,” and the Farsi word for twenty should include something resembling the word for two (do).

You are an excellent counter! Now you can easily count to 40 very quickly, just like the speaker in the next clip.

Well, just kidding. The truth is that your Farsi counting efforts still need some work. But don’t feel bad: you didn’t have much practice. And I hope you have learned some important lessons about learning to count, particularly how daunting the task must be for a young child.